介绍:

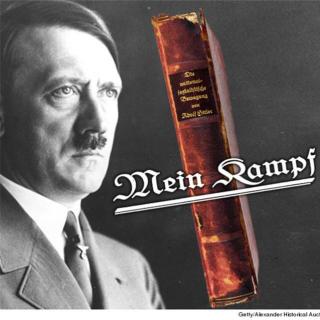

The Japanese cabinet deserves plaudits for uncovering hitherto undiscovered passages in Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf of such educational value that they could be used in the nation’s classrooms. The cabinet, in its wisdom, confirmed on April 14 that Mein Kampf can be classified as appropriate teaching material for schools on the proviso that the book, and this requires the greatest discipline not to howl with derision, can not in any way be used to promote racial discrimination.

The book was written during Hitler’s time in prison following his failed 1923 putsch. It is part autobiography, manifesto, anti-semitic diatribe and instructions on how to gain power. It became a bestseller from 1933, selling a total of 12.5m copies. Finding any part of the book that could be useful for pupils would seem difficult and up until now beyond the capabilities of education authorities the world over.

That it should be advocated by the next host of the Olympic games is beyond parody.

Nor can it be considered a great, if poisonous, work of literature. It is dotted with clunky prose, generally poorly written and grammatically incorrect (it has often been called Sein Krampf or “His Cramp”).

Hitler had been registered as living in Munich, which was in the US sector after the war. The Americans passed publication rights to the state of Bavaria. They refused to re-publish it, though it was never technically banned.

The Bavarian copyright expired at the end of 2015, 70 years as per European copyright law after his death. Consequently publication of the book has been legal in Germany since 2016. Indeed it has been republished in heavily annotated form.

The decision came just weeks after the controversial Imperial Rescript on Education in school was given the green light.

The Rescript, issued in 1890, was meant to inoculate a sense of militarism in schools and unquestioning loyalty to the emperor to groom the nation’s youth in a far-right ideology.

American occupation authorities banned formal reading of the Rescript at the end of the war.

Japan’s cabinet in a statement on March 31 said that its use as teaching material (the same classification as for Mein Kampf) “cannot be denied’’.

The Imperial Rescript came into the limelight earlier this year after a video emerged showing three- to five-year-old pupils at an Osaka kindergarten reciting the document.

The kindergarten is at the center of a growing controversy surrounding land it acquired at well below the market value and a donation it allegedly received from Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s wife.

Nor is the Mein Kampf episode the first time that Japanese politicians have raised the spectre of Nazi Germany. In 2013, deputy prime minister Taro Aso refused to resign despite having to retract comments suggesting the country should follow the Nazi example in changing the country's constitution.

Japan, he said, should learn from how the Nazi party changed Germany's constitution before WWII before opposition was organized to prevent them, and for suggesting that Japanese politicians should avoid controversy by making quiet visits to Tokyo's Yasukuni war shrine, where militarism, and Japan’s wartime role, is celebrated.

上一期: Stamping out an unsightly pollutant----消灭烟头的好方法

下一期: 你经历过那些囧事?My precious dignity – gone with the wind

下一期: 你经历过那些囧事?My precious dignity – gone with the wind

大家还在听